Shariah Principles in ESG

Written by Dr Hazik Mohamed, Managing Director, Stellar Consulting Group

ABSTRACT

In this paper, we explore how economic policy to support sustainability can coordinate efforts to tackle climate risk, overcome environmental challenges and ensure human security. The financial system faces very significant risks posed by climate change, as well as the transition to a low carbon economy. As such, the ESG framework as it is needs to be enhanced in order to be itself effective and sustainable. Hence, we propose an enhanced ESG framework that is grounded in strong Islamic fundamentals to anticipate gaps that can be exploited. Considering human relationships with the natural world from the perspective of Islamic teachings holds great promise for rethinking resource management and preservation. A fundamental role of humans in Islam is that of trustees of creation. The need to achieve sustainable economic development globally and its transition to a low-carbon economy requires strong policies and initiatives to drive green and sustainable finance for the purpose of achieving public policy objectives effectively.

1.0 Introduction: Sustainability Guidelines and Frameworks

For global climate targets to be met, the policy mix must finance sustainable and green investments as well as limit capital for detrimental actions. The absence of regulations may result in financial institutions allocating their capital to activities that are harmful to the environment and society (Dikau & Volz, 2018). To improve efficiency, government intervention is needed to improve environmental and social returns, which differ from private returns. It is imperative that regulatory institutions play a role in developing policies and regulations to support decarbonization efforts, including carbon pricing mechanisms, renewable energy standards, and energy efficiency regulations. As such it is necessary for them to develop a sustainable finance toolkit that consists of a range of policy measures and tools that they can use to promote sustainability and address ecological and shared collective risks within the financial system.

The central authorities within the global and national financial system places them in a powerful position to encourage sustainability through their advocacy, research, participation in and support for international and national initiatives to develop standards, guidelines and charters. Some of them are listed as follows:

- The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)

- The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Risks (TCFR)

- The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) which develops climate scenarios for use by central banks and other financial institutions for scenario analyses

- The Green Bond/Sukuk Principles (and national green bond/sukuk guidelines and frameworks)

- The Green and Sustainability-Linked Loan Principles

- Initiatives to harmonise sustainability standards (such as that led by the IFRS Foundation)

In many countries, national central bank-led green and sustainable finance guidelines have begun to emerge, developed by central banks and financial regulators themselves or often in co-operation with finance sector bodies and other stakeholders.

The IFC’s Sustainable Banking Network , which focuses on sustainable banking, has released green finance guidelines, principles, or roadmaps that are not mandatory. Financial regulators and banking associations are part of this knowledge sharing network intended to enhance ESG risk management practices and green lending (Dikau & Volz, 2021). They are possibly the most influential and powerful groups to bring together the world’s leading and most instrumental monetary, economic, and regulatory institutions to support the shift to a green economy.

2.0 Criticism of the Current ESG Framework

The current ESG approach to investing is generally viewed as a ‘positive screening’ or ‘inclusive screening’ approach, in which investments with favourable ESG factors will be identified. There are some investment managers and funds that use ‘negative screening’ in order to avoid sectors like alcohol, gambling, pornography, usury and weapons.

An increasing body of evidence indicates that environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors are positively correlated with investment returns, which may be attributed to several factors, including a long-term approach to business strategy and value creation, as well as avoiding costs resulting from the failure to tackle ESG issues, like litigation arising from environmental effects, poor employee relations, or carbon taxes.

In the context of ESG approaches, a common criticism is that they often focus primarily on “G” (government) rather than “E” (environment) or “S” (social), and ignore “F” (finance), or the problems associated with the interest-based financial system. While the current ESG framework is intended to achieve the SDGs, its financing mechanisms cannot be grounded in mechanisms which are inherently damaging to the basic idea of sustainability. Green and sustainable finance incur large amounts of debt and borrowing and are largely interest-based. Interest-based finance, as we already know, has several issues:

- Exploitation: Interest-based finance can lead to exploitation of borrowers who may be charged high interest rates that they cannot afford. This can lead to a cycle of debt and financial hardship.

- Bias and Inequality: Interest-based finance can exacerbate economic inequality by providing preferential treatment to those who are already wealthy and have access to capital, while leaving those who are poor without access to affordable credit.

- Speculation: Interest-based finance can encourage speculative behavior, where investors focus on short-term gains rather than long-term investment in productive activities. This can lead to financial bubbles and economic instability.

- Ethical concerns: Interest-based finance is considered unethical by some religious groups, who view it as a form of usury or exploitation.

In contrast, Ethical Financing mechanisms are important for several reasons:

- Promotes social justice: Ethical financing mechanisms are designed to promote social responsibility among financial institutions and investors. This means that they encourage financial institutions to be accountable for the consequences of their lending and investment decisions.

- Builds trust: By adhering to ethical financing principles, financial institutions can build trust with their clients and investors. This can help to enhance their reputation and attract more support and commitment.

- Mitigates risk: Ethical financing mechanisms help to mitigate risk by encouraging financial institutions to consider environmental and social factors when assessing investment opportunities. This can help to identify potential risks and avoid investments that could harm the environment or society. They are also structured to share risks instead of transferring them to others, which essentially just moves a problem to somewhere else without dissipating or effectively dealing with it.

- Aligns with stakeholders’ values: Ethical financing mechanisms allow investors and clients to align their investments and financial decisions with their values and beliefs. This can help to ensure that their money is being used to support causes that they care about.

Also, the lack of a common, agreed methodology for calculating ESG scores and ratings is a significant concern for investors, regulators, and others; this can lead to the inclusion of major greenhouse gas emitters (such as airport operators) in ESG indexes and funds because they score very highly on governance. Increasing clarity, consistency, and comparability over time would be achieved through the development of taxonomies, as well as related regulatory intervention (e.g. fund labelling schemes linked to taxonomies).

2.1 Fragility in the Current Financing System

There are several factors contributing to fragility in the current financing systems, including high debt levels, widespread use of financial derivatives and the lack of transparency.

One of the biggest sources of fragility in the financial system is the high levels of debt that many individuals, companies, and governments have taken on. Debt makes the financial system susceptible to sudden changes in economic conditions, such as a recession or a sudden increase in interest rates. An overleveraged company or individual has taken on more debt than it can comfortably service. As a result, they may not be able to weather a recession or other economic shocks. A market downturn can quickly become a financial crisis if too many companies or individuals are overleveraged. An overleveraged company or individual can lose a significant amount of equity with a relatively small loss. Losses can be difficult to recover, causing ripple effects throughout the financial system. Financial contagion can also occur as a result of overleveraging. Heavy-leveraged companies or individuals can cause a chain reaction of defaults among their creditors and counterparties if they default on their debt. This can quickly spread throughout the financial system and cause a wider financial crisis. The financial system is highly interconnected, and problems at one end can quickly spread to other parts. This can lead to a domino effect in which a small problem in one area of the financial system quickly spirals into a larger crisis.

Another source of fragility is the widespread use of derivatives, which are financial instruments whose value is derived from underlying assets such as stocks, bonds, or commodities. Derivatives can be highly complex financial instruments that are difficult to understand and value. This complexity can lead to mispricing and mismanagement of risk, which can result in unexpected losses and destabilize the financial system. Derivatives often involve multiple parties, such as buyers and sellers, and each party may have its own set of obligations and risks. This creates counterparty risk, which is the risk that one party may default on its obligations, triggering a chain reaction of defaults that can spread throughout the financial system. Derivatives also allow investors to take on large positions with a small amount of capital, which increases leverage. This can amplify losses and create systemic risk, as a large number of investors with highly leveraged positions can trigger a financial crisis. While derivatives can be used to manage risk, they can also amplify risk and create systemic vulnerabilities.

Also, the lack of transparency in some parts of the financial system can make it difficult to understand the true level of risk involved in certain investments or transactions. This can lead to mispricing of assets and systemic vulnerabilities. For example, Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) deceptively securitized as investment-grade became junk grade as their components deteriorated, negatively affecting the portfolio as a whole. While securitization of mortgage-backed securities brought liquidity, its underlying exposure could not be traced in repackaged products (Mohamed, 2021).

Financial system fragility is putting ‘people, planet, and prosperity’ in danger. In a globalized and highly connected world, addressing the root causes of multidimensional fragility inherent in the conventional interest-based financial system is essential for sustainable development and economic growth. The enhanced ESG(F) framework can be developed to guide Green Finance and implement Sustainable Finance.

2.2 The Anti-fragility and Sustainability of Risk-sharing (Islamic) Finance

The risk-sharing cornerstone of Ethical Finance can promote anti-fragility by making the financial system more resilient to shocks. When investors and borrowers share risks, it means that losses are spread more evenly throughout the system. This can reduce the likelihood of financial crises and make the system more resilient to economic shocks.

Risk-sharing finance can promote sustainability by encouraging responsible lending practices. When investors and borrowers share risks, it means that lenders have a greater incentive to ensure that the investments they are making are viable over the long run. This can help to reduce the risks of defaults and non-performing loans, which can undermine the reliability of the financial system.

Risk-sharing finance can also promote sustainability by aligning the interests of investors and borrowers. When investors and borrowers share risks and rewards, it means that they have a common interest in ensuring that the investments they are making are successful over the long-term. In return each party gains any profit, which is shared according to their contributions. This incentivizes all parties to ensure that the ventures (and partnerships) are closely managed and monitored to enable it to succeed for all involved. This can encourage more responsible investment and lending practices, which can help to promote sustainable economic growth.

The ‘rentier’ attitude of capitalistic lenders hampers economic growth and the process of development and progress. In risk-sharing finance as described above, capitalists or lenders take an active role in the borrower’s or entrepreneur’s use of funds from the beginning, which green finance are encouraged to do too. In such arrangements, the know-how of the entrepreneur and the insight of the capitalist or lender are married to achieve shared goals of profitability, and in the case of sustainability, people and planet.

2.3 The Proposed ESG(F) Framework

The proposed Environmental, Social Governance and Financial [ESG(F)] approach is intended to integrate the ESG factors into traditional financial analysis of investments by incorporating (F) ethical finance principles. One or more ESG(F) factors may increase the risk profile of an investment (e.g. if assets are exposed to substantial climate risks), mispricing due to inaccurate interest rates, or the potential returns on offer (e.g. if a company has developed a new, emissions-reducing technology). There is no single method for assessing ESG(F) factors, but in general they should encompass all of the following factors, especially the addition of the financial factors (i.e. the F in the proposed ESG(F) framework):

- Environmental factors: Energy use (and mix of renewable/non-renewable energy), emissions, waste production, impact on the physical environment

- Social factors: Human rights, equality, engagement with and impact on communities, employee relations

- Governance factors: Quality of board and senior management, shareholder rights, transparency and disclosure

- Financial factors: Debt levels, use of risky derivatives and speculative instruments, extent of financial engineering

Whilst there is at the present time a certain attention by many on ecological factors, especially weather-related hazards and opportunities, social and governance factors are often interlinked with these; for example, the effects of a firm’s activities on communities, and its approach to the disclosure of climate-related risk when we refer more holistically to sustainable finance. ESG(F) is generally seen as a ‘positive screening’ or ‘inclusive screening’ approach to investing, as investments will be identified by their favourable ESG(F) factors.

3.0 Incorporating the Shariah in Sustainable Finance Initiatives

Regulatory macroprudential policies are intended to mitigate systemic risks that threaten financial stability. Such policy tools do so by preventing the excessive build-up of systemic risk resulting from factors such as asset price bubbles or excessive risk-taking by banks. Examples of macroprudential policies include restrictions on certain types of lending, or increased capital requirements for certain types of assets. Regulatory frameworks should incorporate climate and environmental risks to provide cover for deficiencies in micro-prudential regulation and macroeconomic policy.

3.1 Banking and Financial Services

By integrating Islamic Sustainable Finance principles and practice into their strategies, activities and operations, banks have a key role to play in supporting their clients’ transitions towards a more sustainable, low-carbon world, and the transition to net zero overall. Not only does this help banks to mitigate climate-related and other risks, it presents a substantial commercial opportunity for financial institutions too, as we explore in this and the following unit. Despite the recent growth in green and sustainable finance, however, the banking sector still often contributes to increasing greenhouse gas emissions and other social harms rather than reducing them.

Alongside risk management and commercial opportunities, there is a growing consensus that banks should increase their green and sustainable finance activities for ethical and societal reasons. Civil society organisations such as ShareAction put pressure on banks to accelerate their alignment with the objectives of the Paris Agreement, and other sustainability goals. ShareAction’s 2020 ‘Banking on a Low-Carbon Future’ report ranks and compares the top 20 global banks in terms of their green and sustainable efforts. Overall, the report found that most banks were not doing enough, with the majority of banks opting for a business-as-usual approach rather than re-aligning their strategies and activities to support green and sustainable objectives. Some US$3.8 trillion of financing had been provided by 60 global banks to fossil fuel companies between 2015 and 2020, significantly outweighing their flows of finance to emissions reduction and other sustainable objectives. On a positive note, however, the ShareAction report found that it was possible for a bank to drastically improve its performance in this area in a relatively short period of time as, for example, Lloyds Banking Group has done.

3.1.1 Shariah Principles of Sustainable Banking

In recent years, moves to incorporate environmental and broader sustainability factors into the banking system have gathered pace. These moves have been driven by a combination of market forces, evolving policy and regulation and changing customer, employee and investor attitudes, which have led banks to consider environmental, social and governance risks and opportunities in their strategies, operations and activities (UNEP FI, 2019). Amongst the most significant initiatives, building on the success of the Principles for Responsible Investment and Principles for Sustainable Insurance are the UN Principles for Responsible Banking, (PRB) launched at the UN General Assembly in 2019.

The Islamic Finance industry should similarly concretize its principles that can be reflected as responsible banking in the form of Principles of Sustainable Islamic Banking (PSIB). These values which are already being practiced can be formally recognized as the industry’s view of professional banking upheld by customer focus, resolute leadership, novel management, and ethical professionalism.

Islamic banks can benefit from the PSIB’s framework, tools, and peer network that helps them integrate Shariah stewardship into green and sustainable finance principles. This echoes the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement in guiding their strategies and activities and tying their business plans with societal goals.

The UN PRB have been developed as principles for all conventional banking organisations (UNEP FI, 2016; 2019). For the PSIB to drive and support a culture of responsible, sustainable banking, alignment driven by consensus is needed at the industry as well as the institutional levels but more profoundly at the individual level:

- Industry level: policymakers, regulators and industry trade associations leading a collective approach to endorsing and implementing the PSIB

- Institutional level: signatories leading by example and sharing good practice

- Individual level: professional bodies and educators embed these standards and qualifications, and explain how they can be demonstrated in banking practice on a daily basis.

Mainstreaming Islamic Green and Sustainable Finance – including the Principles of Sustainable Islamic Banking (PSIB) – needs to be led, ultimately, by individuals committed to change. This means changing their individual professional practice, the practice of others in their organisation and, ultimately, the practice of the organisation itself. Financial services play a crucial role in supporting the transition to a sustainable, socially just world, and the Islamic Finance sector needs more Green and Sustainable Finance professionals. To develop and implement financial products, services, and tools that will mobilise capital to support that transition, address climate-related and societal risks, and help customers and communities invest directly in green finance, finance professionals and Shariah advisory committees must acquire relevant knowledge and skills.

3.2 Capital Market Initiatives

A loan-to-value (LTV) or loan-to-income (LTI) cap restricts how much debt a borrower can take on based on the value of the asset or income of the borrower. In the perspective of net zero, these caps can be used to encourage the development of energy-efficient buildings and other types of green projects.

One way to apply LTV and LTI caps to green finance is to set higher caps for loans used to finance energy-efficient buildings and other types of green projects. For example, a borrower may be able to borrow up to 90% of the value of a property for energy-efficient buildings, compared to 80% for conventional structures.

Another way to apply LTV and LTI caps to green finance is to offer lower interest rates for loans used to finance energy-efficient buildings and other types of green projects.

Additionally, authorities could also use LTV and LTI caps to limit the amount of debt that can be taken on by developers and investors in green projects, which could help to reduce the risk of defaults and financial instability.

3.2.1 Asset-backed Securitization

Asset-backed securities (ABSs) are a type of debt product, similar to a bond. In this case, an issuer (often, but not always, a financial institution) makes (or buys) a range of loans that will finance green and sustainable projects or activities, bundles together (‘securitises’) the revenues from those loans, and issues securities backed by that revenue. Bundling together revenues from such loans to create larger securities allows them to be traded with investors. The individual loans are usually relatively small, illiquid, and cannot be individually traded. Securitisation diversifies the risk of investing in the underlying loans, provided the pool of loans is itself sufficiently diversified and not highly correlated.

The main advantage of securitisation for green and sustainable finance is that it supports the development of smaller organisations for whom the cost and complexity of issuing a green bond, or similar debt instrument, would be a significant barrier to growth (ICMA, 2020). Therefore, green bond issuers tend to be sovereigns, municipalities, financial institutions and large, often publicly listed corporations.

A ‘benchmark’ bond is usually classed as one with a face value of US$500 million, or similar. A large corporate issuer may easily identify eligible use of proceeds for such an amount, but a smaller organisation may only require a fraction of this. For this reason, securitisation and the issue of asset-backed securities can be particularly important in supporting the development of green and sustainable finance in emerging markets; however, it requires well-developed local capital markets with the capacity and capability to support the bundling and marketing of the securities.

3.2.2 Green Sukuk Indices

A stock exchange listing of green and sustainable bonds brings together all the bonds that meet an exchange’s criteria for inclusion. Whilst in the early stages of the development of the green sukuk market such lists were small, and issues were often similar (and therefore easily comparable), the rapid growth of the green and sustainable sukuk market means that listings can be lengthy and encompass a wide range of different green and sustainable sukuk types.

There are several advantages to investors and others of green and sustainable sukuk indices, which help to explain their increasing number and diversity, including:

- As the great majority of global assets under management are passive investments that track indices, green sukuk indices are an important mechanism to ensure that investments in green and sustainable sukuks are accessible to mainstream, passive funds

- Developing a financial performance history for green and sustainable sukuk as an asset class, enables investors (and potential investors) to compare performance of particular sukuk against one or more benchmarks

- Enabling the development of a range of green and sustainable sukuk index funds (discussed in the next section), facilitating investment in this asset class and widening the pool of investment capital available to issuers

Table 1: Overview of Major Green Sukuk Indices

| Index | Investment Grade | Sukuk Types | Coupon | Sustainability Criteria |

| Dow Jones Sustainability Sukuk Index | Investment grade only | Corporations, sovereigns, and supranationals, and the sukuk may be issued in various structures, including mudarabah, musharakah, wakalah, ijarah. | Fixed-rate, floating-rate, and hybrid | Specific sustainability criteria established by the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices |

| MSCI Global Islamic Green Bond Index | Investment grade only | Corporations, sovereigns, and supranationals, and in various structures, including mudarabah, musharakah, wakalah, ijarah. | Fixed-rate, floating-rate, and hybrid | Specific sustainability criteria established by MSCI ESG Research |

| S&P Green Sukuk Index | Investment grade only | Corporations, sovereigns, and supranationals, and in various structures, including mudarabah, musharakah, wakalah, ijarah. | Fixed-rate, floating-rate, and hybrid | Environmental sustainability criteria established by the Climate Bonds Initiative |

| Nasdaq Dubai Green Sukuk Index | Investment grade only | Corporations, sovereigns, and supranationals, and in various structures, including mudarabah, musharakah, wakalah, ijarah. | Fixed-rate, floating-rate, and hybrid | Specific environmental sustainability criteria established by Nasdaq Dubai |

Source: Author’s Own

3.3 Investment Initiatives

For Islamic investing, it can be referred to as a values-based approach to investing and investment decision-making involving financing that follows ethical, moral, and social principles, based on religious and philosophical principles, as well as profit considerations. Transactions must be based on economic activity rather than financial engineering, and money should be used to create social value, not just wealth. This is combined with reducing or eliminating investments in harmful sectors and firms, which in Islamic terms are deemed as non-Shariah-compliant. In line with these objectives, Islamic investments should also deliver positive environmental and social benefits and support the transition to a more sustainable world. The aim is to generate financial returns, by reducing climate, environmental and other sustainability risks and taking advantage of the opportunities from the transition to net zero, as well as a positive impact on the environment and for society.

An Environmental, Social Governance and Financial [ESG(F)] approach is intended to integrate these four factors into traditional financial analysis of investments. One or more ESG(F) factors may increase the risk profile of an investment (e.g. if assets are exposed to substantial climate risks), mispricing due to inaccurate interest rates, or the potential returns on offer (e.g. if a company has developed a new, emissions-reducing technology). There is no single method for assessing ESG(F) factors, or for labelling an investment or fund as ‘ESG(F)’, but in general they might encompass one or more of the following factors:

- Environmental factors: Energy use (and mix of renewable/non-renewable energy), emissions, waste production, impact on the physical environment

- Social factors: Human rights, equality, engagement with and impact on communities, employee relations

- Governance factors: Quality of board and senior management, shareholder rights, transparency and disclosure

- Financial factors: Leveraging, speculative instruments, type of debt and its levels

Whilst there is at the present time a strong focus by many on environmental factors, especially climate-related risks and opportunities, social and governance factors are often interlinked with these; for example, the effects of a firm’s activities on communities, and its approach to the disclosure of climate-related risk when we refer more holistically to sustainable finance.

3.3.1 Shariah Principles of Responsible Investment

The term ‘Responsible Investment’ is used to describe an approach to investment decision-making informed by and aligned with the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (2019, 2021) and refers to an active approach to incorporating ESG(F) factors into investment decision-making, strategies and engagement with investors and investees. The Principles are voluntary and ambitious, and the UN lists suggested actions to incorporate environmental, social, governance and financial [ESG(F)] factors into investment analysis and decision-making. These Principles can be modified to incorporate the Shariah in responsible investing.

‘Socially Responsible Investment (SRI)’ describes an active approach to investment and investment decision-making, involving the selection or elimination of investments based on ethical guidelines and SRI ‘screens’ determined by the investor or investment manager, such as alcohol and tobacco, gambling, human rights and environmental impact. It is comparable to ESG(F) in many ways, although tends to lack a similar focus on governance, as well as to the ‘ethical investment’ approach. Traditionally, SRI approaches were based on ‘negative screening’, i.e. the avoidance and exclusion of shares, securities, funds and other assets that conflicted with the investor’s beliefs and personal values, with investors often accepting lower returns. More recently, SRI approaches adopt positive screening too, seeking to identify opportunities to invest, rather than investments to avoid.

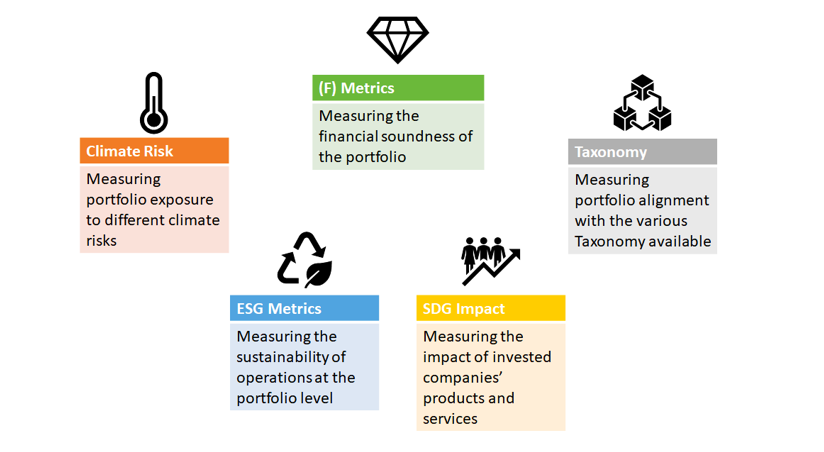

Figure 1: Indicators to be Measured to Assess Islamic Sustainability in Portfolios

For (F) Metrics, values-based sustainability like financial stability and economic justice aspects of financing (F) are measured at portfolio level. We are calculating factors such as asset-backed financing, non-interest-based income, exclusion of speculative instruments, and risk-sharing approach.

4.0 Conclusion

The proposed ESG(F) framework enhanced by financial factors provides the durability and resilience to the entire ESG movement because while the Green and UN SDG initiatives aim for “people, planet, prosperity”, they cannot do so holistically without a sound rules-based ethical framework, an equity-based risk-sharing system within our economies, towards net zero goals. Indeed, policy and regulatory improvements are critical to decarbonization through the right incentives and support, governments can encourage businesses and households to transition to low-carbon, while also spurring innovation and investment in clean technologies and nature-based solutions.

When making decisions, Islamic economics and its finance are guided by scripture, prophetic traditions (Shariah), and juristic pronouncements (fiqh). Additionally, the Islamic financial system must be linked to the real sector of the economy, its debt instruments are asset-backed, its transactions share risks fairly, and its governance adhere to good practices and upholds accountability. These attributes make Islamic finance a crucial pillar to sustainable development and improving SDG initiatives. The triple bottom-line goals (of people, profit, planet) can be enhanced through the adherence of the Shariah, enroute towards a bigger bottom-line ― the pursuit of the ultimate ‘p’ ― Paradise ― as the promised everlasting abode that will encourage all actions now to be accountable, true and committed.

Author’s Bio: Dr Hazik Mohamed

Hazik is a multi-skilled professional with substantial business management and varied experience in strategic, problem-solving, project management and operational leadership roles. He possesses a BSc in Engineering, an MSc in Finance, and a PhD in Islamic Finance, focusing on Behavioural Economics using Game Theory. He has since developed his competencies for various applications, including policy development, corporate product/service innovation and business advisory for digital applications. Hazik has over 24 years of working experience, where he has worked on an array of international consulting projects. His past clients include ASEAN Secretariat, national financial offices, and the UNCDF. These project-based consultancy include business model reviews, capacity readiness assessments, innovative solution conceptualizations, greening MSMEs, sustainability road-mapping and market-based representation. As a sought-after trainer, he has designed and delivered various professional certification programs (such as “Islamic FinTech” endorsed by MDEC and USM; supported by AAOIFI CPD hours) at iFINTELL Business Intelligence in Malaysia, and “Fintech and Digital Transformation in Banking and Finance” supported by Institute of Banking and Finance (IBF) for Sapience Consulting in Singapore. As an adjunct faculty, he has delivered the core economics and finance courses for Putra Business School in its MBA program: “Business Economics”, “Corporate Finance”, “International Finance”, “Security Analysis and Portfolio Theory”. He crafted the university’s elective “Digital Transformation” and “FinTech” courses for its MBA and MSc programs. At the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS), he taught: “Managerial Economics”, “Economic Ideas and Models for Business” and “Essentials of Financial Management” for their undergraduate program. As an author, Hazik has published with three different international publishers: “Belief and Rule Compliance” (Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier, 2018) on behavioural economics; “Blockchain, Fintech and Islamic Finance” (De|Press, an imprint of De Gruyter, 2019) and “Beyond Fintech” (World Scientific, 2021) on the trajectory of frontier technologies used in finance and other sectors. Hazik regularly contributes thought leadership articles to industry-specific magazines like The EDGE Markets and SME Asia Magazine, as well as reputable journals worldwide.

REFERENCES

- BIS (2020). The Basel Committee’s Initiatives on Climate-Related Financial Risks. https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp201014.htm

- Carney, M. (2021). Building a Private Finance System for Net Zero – Priorities for Private Finance for COP 26. https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/COP26-Private-Finance-Hub-Strategy_Nov-2020v4.1.pdf

- CISL & UNEP FI (2014). Stability and Sustainability in Banking Reform: Are Environmental Risks Missing in Basel III. https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/resources/publication-pdfs/stability-andsustainability-basel-iii-final-report.pdf

- European Banking Authority (2019). EBA Action Plan on Sustainable Finance. https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/documents/files/document_library/EBA%20Action%20plan%20on%20sustainable%20finance.pdf

- European Commission (2021). 2030 Climate Target Plan. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/eu-climate-action/2030_ctp_en

- European Securities and Markets Authority (2020). Strategy on Sustainable Finance. https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma22-105-1052_sustainable_finance_strategy.pdf

- Green Finance Institute (2020). Financing the Green Recovery with Launch of World’s First Green Finance Education Charter. https://www.greenfinanceinstitute.co.uk/financing-the-green-recovery-withlaunch-of-worlds-first-green-finance-education-charter/

- International Capital Markets Association (2021). Green Bond Principles (GBP) (online). Available at: https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2021-updates/Green-Bond-Principles-June-2021-140621.pdf

- International Capital Markets Association (2020). Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles (online). Available at: https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/June-2020/Sustainability-Linked-Bond-Principles-June-2020-171120.pdf

- IISD: SDG Knowledge Hub (2020). NDCs from UK, Switzerland, Costa Rica Reiterate Net Zero Goals. https://sdg.iisd.org/news/ndcs-from-uk-switzerland-costa-rica-reiterate-net-zero-goals/

- Mohamed, H. (2021). Decentralizing Finance via Cryptocurrencies, Tokenization of Assets and Peer-to-Peer Platforms. IJIE: International Journal of Islamic Economics, [S.l.], v. 3, n. 1, p. 1-16, July 2021. ISSN 2686-2166.

- OECD (2018). Centre on Green Finance and Investment. http://www.oecd.org/cgfi/

- OECD (2021). Framework for the SDG Aligned Finance. https://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainabledevelopment/Framework-for-SDG-Aligned-Finance-OECD-UNDP.pdf

- Portfolio Decarbonization Coalition (2021). Latest Annual Report: 32 Investors Representing Over US$8 Bn in Decarbonization Commitments Detail Progress Made. Available at: https://unepfi.org/pdc/

- Principles for Responsible Investment & UNEP FI (2020). Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century: Final Report. Available at: https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=11972

- Principles for Responsible Investment (2019) What are the Principles for Responsible Investment? Available at: https://www.unpri.org/pri/what-are-the-principles-for-responsible-investment

- Principles for Responsible Investment (2020). Annual Report 2020. Available at: https://www.unpri.org/annual-report-2020/deliveringour-blueprint-for-responsible-investment/responsible-investors/support-investors-incorporating-esg-issues

- UNDP (2021). SDG Impact Standards for Bonds. https://sdgimpact.undp.org/sdg-bonds.html

- UNEP FI (2019). Commitment to Climate Action. https://www.unepfi.org/banking/bankingprinciples/collective-commitment/

- UNEP FI (2016). Guide to Banking and Sustainability – Edition 2 https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/guide_banking_statements.pdf

- World Bank (2019). 10 Years of Green Bonds: Creating the Blueprint for Sustainability for Capital Markets. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2019/03/18/10-years-ofgreen-bonds-creating-the-blueprint-for-sustainability-across-capitalmarkets

- World Bank Group (2020). Pioneering the Green Sukuk: Three Years On. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34569/Pioneering-the-Green-Sukuk-Three-Years-On.pdf